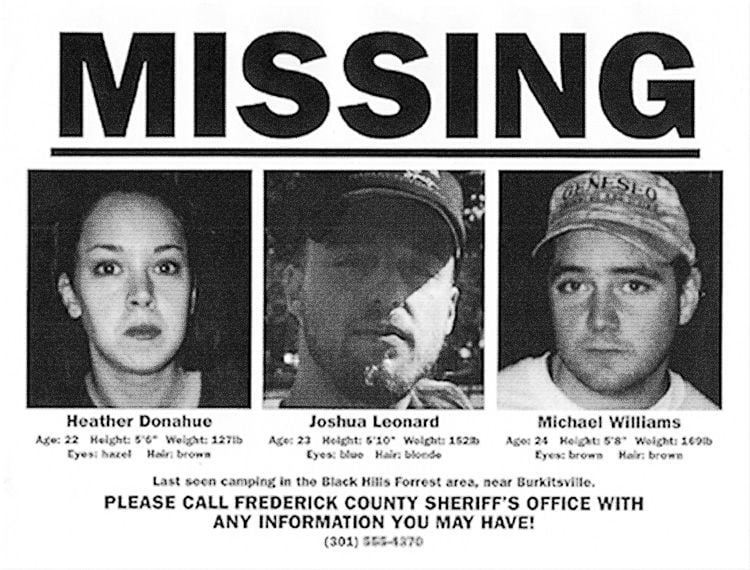

The Blair Witch Project was a media sensation in 1999. The advertising for the film was intense and immersive in groundbreaking ways. Not only was the website experience “innovative,” as Telotte discusses in “The Blair Witch Project Project,” but there were also marketing gimmicks implying that the footage might be real. Up until release, the marketing team kept things ambiguous regarding what was true and what was fiction. The website had fake journal entries and other “evidence.” They even released a second fake documentary about the film students, featuring interviews with family members and mentors grieving them. The actors had to pretend to be dead. Some people went into the film legitimately believing that the footage was real.

The documentary above aired on the Sy-Fy channel in anticipation of the film. Of course, none of this is real (not the footage, obviously, but also not the folklore).

This brief interview with Heather Donahue in 2016 talks a bit about that experience of “playing dead” before the release:

Tell me about what it was like when the movie came out and became the phenomenon it did. Was it weird to suddenly be so famous?

Well you have to understand, we were supposed to be dead. And that was really hard.

Did you have friends or family that were contacting you asking if everything was okay?

My mom got sympathy cards.

Real ones?

Yeah.

Holy shit.

Yeah. It was definitely effective. It was very hard as a young actress where you did something where you were really proud of your work and you feel like you did a really good job, and then you’re kind of in this really stuck situation where you’re an overnight success, but you’re dead. It even said on my IMBD page that I was dead. It said Heather Donahue: Deceased.

I thought, “No! I thought this was going to be an opportunity.” It was crazy.

You guys truly had the ability to see what it would be like after you died.

I got to see what it would be like to be world famous and dead, at the same time, which is a weird thing, especially when you are 24. I remember I bought this $1,000 1984 Toyota Celica GT when I first moved to L.A. I was still driving that when the movie came out, and it had a blown head deck, so it would overheat all the time. One time, the engine overheated under a billboard with my face on it. So I pulled over on the street on La Cienega Blvd under a billboard with my face on it, while my shitty car is giving out. Who gets to have an experience like that? It was surreal. So in that way, I’m very grateful.

The viral marketing campaign was “groundbreakingly” immersive (and manipulative). The ethics of this are debatable. But the film experience itself is also especially immersive when watched in a movie theater. The ambient sounds during the night—such as the footsteps cracking “all around” and the distorted voices—surround you in a darkness that simulates the darkness of the woods in which the characters are lost. The film is atmospheric and that translates well to a theater experience. Moreover, because the found footage format requires you to see through a character’s eyes at all times, to essentially share a body with them, you’re grounded in that space. Conventional camerawork frames you as an observer; found footage camerawork frames you as a participant. Some people even get motion-sickness, as if on a roller coaster ride.

As Heather notes in this 1999 promotional interview, what makes Blair Witch work for so many viewers is its rawness. You can’t go in “expecting Scream” (the other big horror movie sensation of this era, which we aren’t watching). It matters that the most popular horror films of the 90s were bloodier and more gratuitous sequels to 80s slashers, and realist thrillers like Silence of the Lambs. Blair Witch was different. The film is intelligent low-budget filmmaking; it uses the power of suggestion to its advantage. Most of the film is improvised; the actors were given a scenario, but no script. Some of the film’s stark minimalism was “accidental” due to the budget constraints, but arguably ended up working out for the better; for example, when Heather screams “What the fuck is that?” the camera was supposed to pan to a figure in white, but it didn’t happen, and they never reshot it; the original idea for how Heather would find Mike in the basement was much more spectacularly violent than simply facing the wall.

Like most uber-hyped film releases, and most minimalist horror entries, The Blair Witch Project is divisive; people tend to either love or hate its “rawness.” My friends and I were super excited to see it when it came out, but because we weren’t yet old enough in 1999 to go to a R-rated movie, my mom and uncle reluctantly agreed to “accompany” us. The theater was packed, so we sat pretty far apart from them. I recall loving every low-fi minute of it. Much of the imagery stuck with me, and still does to this day: the child’s handprints on the walls (the theater audibly gasped at this); the satchel with the eyes, teeth, and tongue; the sound of the children crying at night; Mary describing the woman with black hair and a body like a horse. There was something poetic about it all. It was quite memorable for me at 14, when I was already pretty “into” horror movies.

I remember the first thing my uncle said when we reunited outside the theater was “That was the stupidest movie I have ever seen.”

While I wouldn’t say this film is the “smartest” we’ve watched thus far, it’s worth noting that there is still some interesting cultural and historical critique present in this film. It’s subtle, but worth considering within its proper cultural context. Several times, for example, Gen X-er Heather says it’s impossible to get lost in America because we’ve destroyed so much wilderness. There are allusions, such as the history of witch trials, and Josh says a site looks like an “Indian Burial Ground,” a horror trope we’ve already noted calls attention to colonialist violence. Consider other moments when the film offers sociocultural or historical commentary or context, or grasps at meaning, or reminds us that it’s part of a social fabric.

Love it or hate it, The Blair Witch Project’s influence and impact on the horror genre and its marketing cannot be denied. It was one of the first movies to use a website as a primary marketing tool, and though it wasn’t the first found footage film, its popularity catalyzed the found footage trend that led to other popular horror franchises like Paranormal Activity, V/H/S, and [REC] (from Spain). It’s even changed our cultural language, to some extent; we might joke that our cat staring at the wall is “Blair Witching,” for example. The film also perhaps reminded studios that horror didn’t need excessive or gratuitous effects to be profitable ventures.

If you haven’t seen it before, but have seen other found footage horror films, The Blair Witch Project might be disappointing; as with The Exorcist in 1973, there’s something to be said for Being There. Nonetheless, it’s the only found footage film we’re watching, and even if you don’t like it, I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the unique appeal of found footage horror and why this film was popular in 1999, as well as why it has had such a long cultural memory.